Meiji Restoration

This article needs additional citations for verification. (November 2023) |

| Part of the end of the Edo period | |

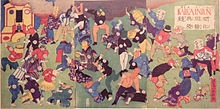

Promulgation of the new Japanese constitution by Emperor Meiji in 1889 | |

| Date | 3 January 1868 |

|---|---|

| Location | Japan |

| Outcome | Overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate |

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Japan |

|---|

|

The Meiji Restoration (Japanese: 明治維新, romanized: Meiji Ishin), referred to at the time as the Honorable Restoration (御維新, Goishin), and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ruling emperors before the Meiji Restoration, the events restored practical abilities and consolidated the political system under the Emperor of Japan.[2] The goals of the restored government were expressed by the new emperor in the Charter Oath.

The Restoration led to enormous changes in Japan's political and social structure and spanned both the late Edo period (often called the Bakumatsu) and the beginning of the Meiji era, during which time Japan rapidly industrialized and adopted Western ideas and production methods.

Foreign influence

[edit]In 1853, Commodore Matthew C. Perry arrived in Japan. A year later Perry returned in threatening large warships with the aspiration of concluding a treaty that would open up Japanese ports for trade.[1] Perry concluded the treaty that would open up two Japanese ports (Shimoda and Hakodate) only for material support, such as firewood, water, food, and coal for U.S. ships. The Convention of Kanagawa was signed in 1854 and opened up trade between the United States and Japan. Later, Japan reluctantly expanded its trade deals to France, Britain, the Netherlands and Russia due to American pressure. These treaties signed with Western powers came to be known as Unequal Treaties as Japan lost control over its tariffs while Western powers took control over Japanese lands. In 1858, Townsend Harris, ambassador to Japan, concluded the treaty, opening Japanese ports to trade. Figures like Shimazu Nariakira concluded that "if we take the initiative, we can dominate; if we do not, we will be dominated", leading Japan to "throw open its doors to foreign technology."[2]

After the humiliation of the Unequal Treaties, the leaders of the Meiji Restoration (as this revolution came to be known), acted in the name of restoring imperial rule to strengthen Japan against the threat of being colonized, bringing to an end the era known as sakoku. The word "Meiji" means "enlightened rule" and the goal was to combine "modern advances" with traditional "eastern" values (和魂洋才, Wakonyosai).[3] The main leaders of this were Itō Hirobumi, Matsukata Masayoshi, Kido Takayoshi, Itagaki Taisuke, Yamagata Aritomo, Mori Arinori, Ōkubo Toshimichi, and Yamaguchi Naoyoshi.

Imperial restoration

[edit]The foundation of the Meiji Restoration was the 1866 Satsuma-Chōshū Alliance between Saigō Takamori and Kido Takayoshi, leaders of the reformist elements in the Satsuma and Chōshū Domains at the southwestern end of the Japanese archipelago. These two leaders supported the Emperor Kōmei (Emperor Meiji's father) and were brought together by Sakamoto Ryōma for the purpose of challenging the ruling Tokugawa shogunate (bakufu) and restoring the Emperor to power. After Kōmei's death on 30 January 1867, Meiji ascended the throne on February 3. This period also saw Japan change from being a feudal society to having a centralized nation and left the Japanese with a lingering influence of modernity.[4]

In the same year, the koban was discontinued as a form of currency.

End of the Tokugawa shogunate

[edit]

The Tokugawa government had been founded in the 17th century and initially focused on reestablishing order in social, political and international affairs after a century of warfare. The political structure, established by Tokugawa Ieyasu and solidified under his two immediate successors, his son Tokugawa Hidetada (who ruled from 1616 to 1623) and grandson Tokugawa Iemitsu (1623–51), bound all daimyōs to the shogunate and limited any individual daimyō from acquiring too much land or power.[5] The Tokugawa shogunate came to its official end on 9 November 1867, when Tokugawa Yoshinobu, the 15th Tokugawa shōgun, "put his prerogatives at the Emperor's disposal" and resigned 10 days later.[6] This was effectively the "restoration" (Taisei Hōkan) of imperial rule – although Yoshinobu still had significant influence and it was not until January 3, the following year, with the young Emperor's edict, that the restoration fully occurred.[7] On 3 January 1868, the Emperor stripped Yoshinobu of all power and made a formal declaration of the restoration of his power:

The Emperor of Japan announces to the sovereigns of all foreign countries and to their subjects that permission has been granted to the Shōgun Tokugawa Yoshinobu to return the governing power in accordance with his own request. We shall henceforward exercise supreme authority in all the internal and external affairs of the country. Consequently, the title of Emperor must be substituted for that of Taikun, in which the treaties have been made. Officers are being appointed by us to the conduct of foreign affairs. It is desirable that the representatives of the treaty powers recognize this announcement.

Shortly thereafter in January 1868, the Boshin War started with the Battle of Toba–Fushimi in which Chōshū and Satsuma's forces defeated the ex-shōgun's army. All Tokugawa lands were seized and placed under "imperial control", thus placing them under the prerogative of the new Meiji government. With Fuhanken sanchisei, the areas were split into three types: urban prefectures (府, fu), rural prefectures (県, ken) and the already existing domains.

On March 23 the Dutch Minister-Resident Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek and the French Minister-Resident Léon Roches were the first European envoys ever to receive a personal audience with Meiji in Edo (Tokyo).[9][10] This audience laid the foundation for (modern) Dutch diplomacy in Japan.[11] Subsequently, De Graeff van Polsbroek assisted the emperor and the government in their negotiations with representatives of the major European powers.[12][11]

In 1869, the daimyōs of the Tosa, Hizen, Satsuma and Chōshū Domains, who were pushing most fiercely against the shogunate, were persuaded to "return their domains to the Emperor". Other daimyō were subsequently persuaded to do so, thus creating a central government in Japan which exercised direct power through the entire "realm".[3]

Some shogunate forces escaped to Hokkaidō, where they attempted to set up a breakaway Republic of Ezo; however, forces loyal to the Emperor ended this attempt in May 1869 with the Battle of Hakodate in Hokkaidō. The defeat of the armies of the former shōgun (led by Enomoto Takeaki and Hijikata Toshizō) marked the final end of the Tokugawa shogunate, with the Emperor's power fully restored.[13]

Finally, by 1872, the daimyōs, past and present, were summoned before the Emperor, where it was declared that all domains were now to be returned to the Emperor. The roughly 280 domains were turned into 72 prefectures, each under the control of a state-appointed governor. If the daimyōs peacefully complied, they were given a prominent voice in the new Meiji government.[14] Later, their debts and payments of samurai stipends were either taxed heavily or turned into bonds which resulted in a large loss of wealth among former samurai.[15]

Military reform

[edit]Emperor Meiji announced in his 1868 Charter Oath that "Knowledge shall be sought all over the world, and thereby the foundations of imperial rule shall be strengthened."[16]

Under the leadership of Mori Arinori, a group of prominent Japanese intellectuals went on to form the Meiji Six Society in 1873 to continue to "promote civilization and enlightenment" through modern ethics and ideas. However, during the restoration, political power simply moved from the Tokugawa shogunate to an oligarchy consisting of these leaders, mostly from Satsuma Province (Ōkubo Toshimichi and Saigō Takamori), and Chōshū Province (Itō Hirobumi, Yamagata Aritomo, and Kido Takayoshi). This reflected their belief in the more traditional practice of imperial rule, whereby the Emperor of Japan serves solely as the spiritual authority of the nation and his ministers govern the nation in his name.[17]

The Meiji oligarchy that formed the government under the rule of the Emperor first introduced measures to consolidate their power against the remnants of the Edo period government, the shogunate, daimyōs, and the samurai class.[18]

Throughout Japan at the time, the samurai numbered 1.9 million. For comparison, this was more than 10 times the size of the French privileged class before the 1789 French Revolution. Moreover, the samurai in Japan were not merely the lords, but also their higher retainers—people who actually worked. With each samurai being paid fixed stipends, their upkeep presented a tremendous financial burden, which may have prompted the oligarchs to action.

Whatever their true intentions, the oligarchs embarked on another slow and deliberate process to abolish the samurai class. First, in 1873, it was announced that the samurai stipends were to be taxed on a rolling basis. Later, in 1874, the samurai were given the option to convert their stipends into government bonds. Finally, in 1876, this commutation was made compulsory.[19]

To reform the military, the government instituted nationwide conscription in 1873, mandating that every male would serve for four years in the armed forces upon turning 21 years old, followed by three more years in the reserves. One of the primary differences between the samurai and peasant classes was the right to bear arms; this ancient privilege was suddenly extended to every male in the nation. Furthermore, samurai were no longer allowed to walk about town bearing a sword or weapon to show their status.

This led to a series of riots from disgruntled samurai. One of the major riots was the one led by Saigō Takamori, the Satsuma Rebellion, which eventually turned into a civil war. This rebellion was, however, put down swiftly by the newly formed Imperial Japanese Army, trained in Western tactics and weapons, even though the core of the new army was the Tokyo police force, which was largely composed of former samurai. This sent a strong message to the dissenting samurai that their time was indeed over. There were fewer subsequent samurai uprisings and the distinction became all but a name as the samurai joined the new society. The ideal of samurai military spirit lived on in romanticized form and was often used as propaganda during the early 20th-century wars of the Empire of Japan.[20]

However, it is equally true that the majority of samurai were content despite having their status abolished. Many found employment in the government bureaucracy, which resembled an elite class in its own right. The samurai, being better educated than most of the population, became teachers, gun makers, government officials, and/or military officers. While the formal title of samurai was abolished, the elitist spirit that characterized the samurai class lived on.[21]

The oligarchs also embarked on a series of land reforms. In particular, they legitimized the tenancy system which had been going on during the Tokugawa period. Despite the bakufu's best efforts to freeze the four classes of society in place, during their rule villagers had begun to lease land out to other farmers, becoming rich in the process. This greatly disrupted the clearly defined class system which the bakufu had envisaged, partly leading to their eventual downfall.[22]

The military of Japan, strengthened by nationwide conscription and emboldened by military success in both the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War, began to view themselves as a growing world power.

Centralization

[edit]

Besides drastic changes to the social structure of Japan, in an attempt to create a strong centralized state defining its national identity, the government established a dominant national dialect, called "standard language" (標準語, hyōjungo), that replaced local and regional dialects and was based on the patterns of Tokyo's samurai classes. This dialect eventually became the norm in the realms of education, media, government, and business.[23]

The Meiji Restoration, and the resultant modernization of Japan, also influenced Japanese self-identity with respect to its Asian neighbours, as Japan became the first Asian state to modernize based on the Western model, replacing the traditional Confucian hierarchical order that had persisted previously under a dominant China with one based on modernity.[24] Adopting enlightenment ideals of popular education, the Japanese government established a national system of public schools.[25] These free schools taught students reading, writing, and mathematics. Students also attended courses in "moral training" which reinforced their duty to the Emperor and to the Japanese state. By the end of the Meiji period, attendance in public schools was widespread, increasing the availability of skilled workers and contributing to the industrial growth of Japan.

The opening up of Japan not only consisted of the ports being opened for trade, but also began the process of merging members of the different societies together. Examples of this include western teachers and advisors immigrating to Japan and also Japanese nationals moving to western countries for education purposes. All these things in turn played a part in expanding the people of Japan's knowledge on western customs, technology and institutions. Many people believed it was essential for Japan to acquire western "spirit" in order to become a great nation with strong trade routes and military strength.[26]

Industrial growth

[edit]The Meiji Restoration accelerated the industrialization process in Japan, which led to its rise as a military power by the year 1895, under the slogan of "Enrich the country, strengthen the military" (富国強兵, fukoku kyōhei).

There were a few factories set up using imported technologies in the 1860s, principally by Westerners in the international settlements of Yokohama and Kobe, and some local lords, but these had relatively small impacts. It was only in the 1870s that imported technologies began to play a significant role, and only in the 1880s did they produce more than a small output volume.[27] In Meiji Japan, raw silk was the most important export commodity, and raw silks exports experienced enormous growth during this period, overtaking China. Revenue from silk exports funded the Japanese purchase of industrial equipment and raw materials. Although the highest quality silk remained produced in China, and Japan's adoption of modern machines in the silk industry was slow, Japan was able to capture the global silk market due to standardized production of silk. Standardization, especially in silkworm egg cultivation, yielded more consistency in quality, particularly important for mechanized silk weaving.[28] Since the new sectors of the economy could not be heavily taxed, the costs of industrialisation and necessary investments in modernisation heavily fell on the peasant farmers, who paid extremely high land tax rates (about 30 percent of harvests) as compared to the rest of the world (double to seven times of European countries by net agricultural output). In contrast, land tax rates were about 2% in Qing China. The high taxation gave the Meiji government considerable leeway to invest in new initiatives.[29]

During the Meiji period, powers such as Europe and the United States helped transform Japan and made them realize a change needed to take place. Some leaders went out to foreign lands and used the knowledge and government writings to help shape and form a more influential government within their walls that allowed for things such as production. Despite the help Japan received from other powers, one of the key factors in Japan's industrializing success was its relative lack of resources, which made it unattractive to Western imperialism.[30] The farmer and the samurai classification were the base and soon the problem of why there was a limit of growth within the nation's industrial work. The government sent officials such as the samurai to monitor the work that was being done. Because of Japan's leaders taking control and adapting Western techniques it has remained one of the world's largest industrial nations.

The rapid industrialization and modernization of Japan both allowed and required a massive increase in production and infrastructure. Japan built industries such as shipyards, iron smelters, and spinning mills, which were then sold to well-connected entrepreneurs. Consequently, domestic companies became consumers of Western technology and applied it to produce items that would be sold cheaply in the international market. With this, industrial zones grew enormously, and there was a massive migration to industrializing centers from the countryside. Industrialization additionally went hand in hand with the development of a national railway system and modern communications.[31]

| Year(s) | Production | Exports |

|---|---|---|

| 1868–1872 | 1026 | 646 |

| 1883 | 1682 | 1347 |

| 1889–1893 | 4098 | 2444 |

| 1899–1903 | 7103 | 4098 |

| 1909–1914 | 12460 | 9462 |

With industrialization came the demand for coal. There was dramatic rise in production, as shown in the table below.

| Year | In millions of tonnes |

In millions of long tons |

In millions of short tons |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1875 | 0.6 | 0.59 | 0.66 |

| 1885 | 1.2 | 1.2 | 1.3 |

| 1895 | 5 | 4.9 | 5.5 |

| 1905 | 13 | 13 | 14 |

| 1913 | 21.3 | 21.0 | 23.5 |

Coal was needed for steamships and railroads. The growth of these sectors is shown below.

| Year | Number of steamships |

|---|---|

| 1873 | 26 |

| 1894 | 169 |

| 1904 | 797 |

| 1913 | 1,514 |

| Year | mi | km |

|---|---|---|

| 1872 | 18 | 29 |

| 1883 | 240 | 390 |

| 1887 | 640 | 1,030 |

| 1894 | 2,100 | 3,400 |

| 1904 | 4,700 | 7,600 |

| 1914 | 7,100 | 11,400 |

Destruction of cultural heritage

[edit]The majority of Japanese castles were partially or completely dismantled in the late 19th century in the Meiji restoration by the national government. Since the feudal system was abolished and the fiefs (han) theoretically reverting to the emperor, the national government saw no further use for the upkeep of these now obsolete castles. The military was modernized and some parts of the castles were converted into modern military facilities with barracks and parade grounds, such as Hiroshima Castle. Others were handed over to the civilian authorities to build their new administrative structures.[32] Some however were explicitly saved from destruction by interventions from various persons and parties such as politicians, government and military officials, experts, historians, and locals who feared a loss of their cultural heritage. In the case of Hikone Castle, even though the government ordered its dismantling, it was saved by orders from the emperor himself. Nagoya Castle and Nijo Castle, due to their historical and cultural importance and sheer size and strategic locations, both became official imperial detached palaces, before they were turned over to the local authorities in the 1930s. Others such as Himeji Castle survived by luck.

During the Meiji restoration's shinbutsu bunri, tens of thousands of Japanese Buddhist religious idols and temples were smashed and destroyed.[33] Japan then closed and shut down tens of thousands of traditional old Shinto shrines in the Shrine Consolidation Policy and the Meiji government built the new modern 15 shrines of the Kenmu restoration as a political move to link the Meiji restoration to the Kenmu restoration for their new State Shinto cult.

Outlawing of traditional practices

[edit]In the Blood tax riots, the Meiji government put down revolts by Japanese samurai angry that the traditional untouchable status of burakumin was legally revoked.

Under the Meiji Restoration, the practices of the samurai classes, deemed feudal and unsuitable for modern times following the end of sakoku in 1853, resulted in a number of edicts intended to 'modernise' the appearance of upper class Japanese men. With the Dampatsurei Edict of 1871 issued by Emperor Meiji during the early Meiji Era, men of the samurai classes were forced to cut their hair short, effectively abandoning the chonmage (chonmage) hairstyle.[34]: 149

During the Meiji Restoration, the practice of cremation and Buddhism were condemned and the Japanese government tried to ban cremation but were unsuccessful, then tried to limit it in urban areas. The Japanese government reversed its ban on cremation and pro-cremation Japanese adopted western European arguments on how cremation was good for limiting disease spread, so the Japanese government lifted their attempted ban in May 1875 and promoted cremation for diseased people in 1897.[35]

Use of foreign specialists

[edit]Even before the Meiji Restoration, the Tokugawa Shogunate government hired German diplomat Philipp Franz von Siebold as diplomatic advisor, Dutch naval engineer Hendrik Hardes for Nagasaki Arsenal and Willem Johan Cornelis, Ridder Huijssen van Kattendijke for Nagasaki Naval Training Center, French naval engineer François Léonce Verny for Yokosuka Naval Arsenal, and British civil engineer Richard Henry Brunton. Most of them were appointed through government approval with two or three years contract, and took their responsibility properly in Japan, except some cases. Then many other foreign specialists were hired.

Despite the value they provided in the modernization of Japan, the Japanese government did not consider it prudent for them to settle in Japan permanently. After their contracts ended, most of them returned to their country except some, like Josiah Conder and W. K. Burton.

See also

[edit]- Bakumatsu

- Datsu-A Ron

- Four Hitokiri of the Bakumatsu

- Land Tax Reform (Japan 1873)

- Japanese military modernization of 1868–1931

- Meiji Constitution

- Ōka shugi

Explanatory notes

[edit]- 1.^ Although the political system was consolidated under the Emperor, power was mainly transferred to a group of people, known as the Meiji oligarchy (and Genrō).[15]

- 2.^ At that time, the new government used the phrase "Itten-banjō" (一天万乗). However, the more generic term 天下 is most commonly used in modern historiography.

References

[edit]- ^ Hunt, Lynn (2016). The Making of the West : Peoples and Cultures. Boston : Bedford/St. Martin's, A Macmillan Education Imprint. pp. 712–713. ISBN 978-1-4576-8143-1.

- ^ "Harris Treaty | U.S.-Japan, Diplomacy, Trade | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ Kissinger, Henry, ed. (2012). On China. New York, NY: Penguin Books. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-59420-271-1.

- ^ "The Meiji Restoration and Modernization". Asia for Educators, Columbia University. Columbia University. Retrieved 7 May 2018.

- ^ "Tokugawa Period and Meiji Restoration". History.com. Retrieved 2 March 2018.

- ^ "Meiji Restoration | Definition, History, & Facts". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ "One can date the 'restoration' of imperial rule from the edict of 3 January 1868." Jansen (2000), p. 334.

- ^ Quoted and translated in Satow, Ernest Mason, ed. (2006). A Diplomat In Japan. Yohan classics. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press. p. 353. ISBN 978-1-933330-16-7.

- ^ Keene, Donald (2002). Emperor of Japan: Meiji and His World, 1852-1912. Columbia University Press. p. 133. ISBN 978-0-231-12341-9.

- ^ Scherrer, Daniel (2009). The Last Samurai - Japanische Geschichtsdarstellung im populären Kinofilm (in German). Diplomica Verlag. ISBN 978-3-8366-7199-6.

- ^ a b "From Dejima to Tokyo. Dirk de Graeff van Polsbroek (This study is the first complete history of Dutch diplomatic locations in Japan. It has been commissioned by the Embassy of the Kingdom of the Netherlands in Tokyo)". Archived from the original on 8 March 2023. Retrieved 17 March 2023.

- ^ Het geheugen van Nederland

- ^ "Tokugawa period | Definition & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 14 January 2025. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ David "Race" Bannon, "Redefining Traditional Feudal Ethics in Japan during the Meiji Restoration," Asian Pacific Quarterly, Vol. 26, No. 1 (1994): 27–35.

- ^ a b Gordon, Andrew (2003). A Modern History of Japan From Tokugawa Times to the Present. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 61–62. ISBN 9780198027089.

- ^ Kissinger, Henry, ed. (2012). On China. New York, NY: Penguin Books. p. 79. ISBN 978-1-59420-271-1.

- ^ "Mori Arinori | Meiji Era, Education Reform, Diplomat | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ Federal Research Division (1992). Japan: A Country Study. Library of Congress. p. 38.

- ^ "Mori Arinori | Meiji Era, Education Reform, Diplomat | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ Wert, Michael (26 September 2019). Samurai: A Concise History. Oxford University Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0190932947. Retrieved 7 April 2021.

- ^ "Tokugawa period | Definition & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 14 January 2025. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ "Tokugawa period | Definition & Facts | Britannica". www.britannica.com. 14 January 2025. Retrieved 17 January 2025.

- ^ Bestor, Theodore C. "Japan." Countries and Their Cultures. Eds. Melvin Ember and Carol Ember. Vol. 2. New York: Macmillan Reference USA, 2001. 1140–1158. 4 vols. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Gale. Pepperdine University SCELC. 23 November 2009 [1].

- ^ Shih, Chih-yu (Spring 2011). "A Rising Unknown: Rediscovering China in Japan's East Asia". China Review. 11 (1). Chinese University Press: 2. JSTOR 23462195.

- ^ "The Meiji Restoration and Modernization | Asia for Educators | Columbia University". afe.easia.columbia.edu. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Phipps, Catherine (18 June 2024), "The Treaty Port System in Japan, 1858–1899", Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Asian History, doi:10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-565?d=/10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.001.0001/acrefore-9780190277727-e-565&p=emailagxlmu6dmzi0o, ISBN 978-0-19-027772-7, retrieved 17 January 2025

- ^ Leeuwen, Bas van; Philips, Robin C. M.; Buyst, Erik (2020). An economic history of regional industrialization. Routledge explorations in economic history. London: Routledge. p. 186. ISBN 978-0-429-51012-0.

- ^ Lillian M. Li (1982). "Silks By Sea: Trade, Technology, And Enterprise In China And Silks By Sea: Trade, Technology, And Enterprise In China And Japan". Business History Review. 56 (2): 192–217. doi:10.2307/3113976. JSTOR 3113976.

- ^ Peer Vries (2019). Averting a Great Divergence: State and Economy in Japan, 1868-1937. Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 117–119. ISBN 9781350121683.

- ^ Zimmermann, Erich W. (1951). World Resources and Industries. New York: Harper & Row. pp. 462, 525, 718.

- ^ Yamamura, Kozo (1977). "Success Illgotten? The Role of Meiji Militarism in Japan's Technological Progress". The Journal of Economic History. 37 (1). Cambridge University Press: 113–135. doi:10.1017/S0022050700096777. JSTOR 2119450. S2CID 154563371.

- ^ "Japanese castles History of Castles". Japan Guide. 4 September 2021.

- ^ "Shinbutsu bunri – the separation of Shinto and Buddhism". Japan Reference. 11 July 2019.

- ^ Scott Pate, Alan (2017). Kanban: Traditional Shop Signs of Japan. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0691176475.

In 1871 the Dampatsurei edict forced all samurai to cut off their topknots, a traditional source of identity and pride.

- ^ Hiatt, Anna (9 September 2015). "The History of Cremation in Japan". Jstor Daily.

Further reading

[edit]- Akamatsu, Paul (1972). Meiji, 1868: Revolution and Counter-revolution in Japan. Great revolutions (1st U.S. ed.). New York: Harper & Row. p. 1247. ISBN 978-0-06-010044-5.

- Beasley, W. G. (1972). The Meiji Restoration. Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-0815-9.

- Beasley, W. G. (2000). The Rise of Modern Japan. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-0-312-23373-0.

- Breen, John (1996). "The Imperial Oath of April 1868: Ritual, Politics, and Power in the Restoration". Monumenta Nipponica. 51 (4): 407–429. doi:10.2307/2385417. JSTOR 2385417.

- Craig, Albert M. (1961). Chōshū in the Meiji Restoration. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-12850-7.

- Earl, David Magarey (1981). Emperor and Nation in Japan: Political Thinkers of the Tokugawa Period. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Press. pp. 82–105, 161–192. ISBN 978-0-313-23105-6.

- Harootunian, Harry D. (1970). Toward Restoration: The Growth of Political Consciousness in Tokugawa Japan. Publications of the center for Japanese and Korean studies (1. ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 1–46, 184–219. ISBN 978-0-520-01566-1.

- Jansen, Marius B.; Rozman, Gilbert (2014). Japan in Transition: From Tokugawa to Meiji. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-5430-1.

- Jansen, Marius B. (1994). Sakamoto Ryōma and the Meiji Restoration (Morningside ed.). New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-10173-8. Especially chapter VIII: "Restoration".

- Jansen, Marius B., ed. (1996). "The Meiji Restoration". The Cambridge History of Japan. Vol. 5: The Nineteenth Century (Repr ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 308–366. ISBN 978-0-521-22356-0.

- Jansen, Marius B. (2000). The making of modern Japan (PDF). Cambridge, Mass: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00334-7.

- Karube, Tadashi; Noble, David (2019). Toward the Meiji Revolution: The Search for "Civilization" in Nineteenth-century Japan. Japan Library (First English ed.). Tokyo, Japan: Japan Publishing Industry Foundation for Culture. ISBN 978-4-86658-059-3. OCLC 1091359003.

- McAleavy, Henry (September 1958). "The Meiji Restoration". History Today. Vol. 8, no. 9. pp. 634–645.

- McAleavy, Henry (May 1959). "The Making of Modern Japan". History Today. Vol. 9, no. 5. pp. 297–300.

- Murphey, Rhoads (2001). East Asia: A New History (2nd ed.). New York: Longman. ISBN 978-0-321-07801-8.

- Satow, Ernest Mason, ed. (2006). A Diplomat in Japan: The inner history of the critical years in the evolution of Japan when the ports were opened and the monarchy restored, recorded by a diplomatist who took an active part in the events of the time, with an account of his personal experiences during that period. Yohan classics. Berkeley: Stone Bridge Press. ISBN 978-1-933330-16-7.

- Strayer, Robert W.; Nelson, Eric (2016). Ways of the World: A Global History with Sources (3rd ed.). Boston ; New York: Bedford/St. Martin's. p. 950. ISBN 978-1-319-02272-3.

- Najita, Tetsuo (1980). "Restorationism in Late Tokugawa". Japan: The Intellectual Foundations of Modern Japanese Politics. Phoenix book. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 43-68. ISBN 978-0-226-56803-4.

- Totman, Conrad (1980). "From Sakoku to Kaikoku. The Transformation of Foreign-Policy Attitudes, 1853-1868". Monumenta Nipponica. 35 (1): 1–19. doi:10.2307/2384397. JSTOR 2384397.

- Wall, Rachel F. (1971). Japan's Century: An Interpretation of Japanese History Since the Eighteen-fifties. London: Historical Association. ISBN 978-0-85278-044-2.

External links

[edit]- Essay on The Meiji Restoration Era, 1868–1889 on the About Japan, A Teacher's Resource website

- A rare collection of Japanese Photographs of the Meiji Restoration from famous 19th-century Japanese and European photographers